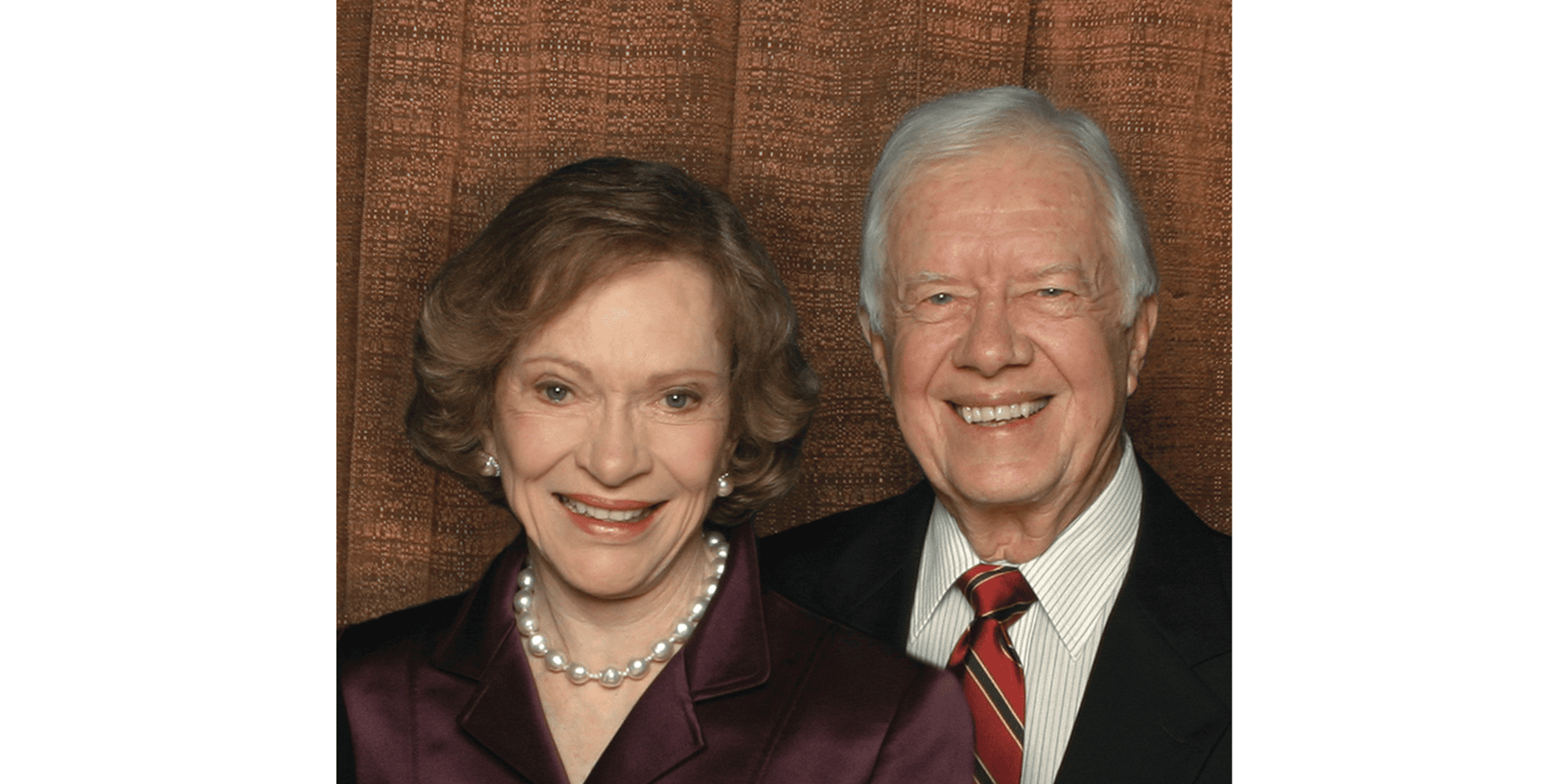

The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award is presented annually by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID) to honor individuals whose outstanding humanitarian efforts and achievements have contributed significantly to improving global public health through domestic and/or international activities.

Established in 1997, the award is named for former President and Mrs. Carter, who as outstanding humanitarians, have worked tirelessly to improve the quality of life for people worldwide. Through their work at The Carter Center, President and Mrs. Carter have worked to resolve conflict peacefully, promote democracy, protect human rights, and prevent and eradicate disease. In recognition of their efforts, President and Mrs. Carter were presented with the first Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award in 1997.

NFID selected Penny M. Heaton, MD, to receive the 2020 Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award for her influence in vaccine development and public health. Dr. Heaton is renowned for leading the development of vaccines that have saved millions of lives, including vaccines for rotavirus, influenza, and meningococcal disease. Her groundbreaking contributions on maternal vaccines have the potential to address important causes of prematurity, stillbirths, and neonatal sepsis. Dr. Heaton is CEO and executive director of the Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute, a non-profit biotechnology organization that applies translational science to combat diseases that disproportionately impact the poor. Dr. Heaton brings a relentless passion, outstanding leadership talent, and industrial-strength rigor to the development of new vaccines. Her distinguished career of developing and enhancing access to lifesaving vaccines to people in economically and socially disadvantaged settings makes her an ideal candidate to receive the award, which honors individuals whose outstanding humanitarian achievements have contributed significantly to improving global public health.

An Interview With Dr. Heaton

What is your greatest professional accomplishment?

To date, it has to be shepherding the rotavirus vaccine, RotaTeq, through to regulatory approval and universal recommendation with my team at Merck and thousands of global partners who shared the same vision—a vaccine against the leading cause of diarrheal disease deaths in children.

While serving in the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), I supported a diarrheal disease surveillance study in western Kenya. After two years, I saw firsthand the devastation wrought by diarrheal diseases in this rural area. Of over 400 infants and young children, more than 50 had died—half had diarrheal disease and half had pneumonia. The solutions we had to offer the parents were so inadequate. Boil your water—but how? Water came from Lake Victoria and wood was scarce. Use latrines–but the nearest were miles away. Just as I was entering a near existential crisis, I received an email recruiting me to a pharmaceutical company that had a rotavirus vaccine entering late-stage development. It hit me—this was a tangible solution that could potentially be a bridge to a better future.

The vaccine development journey was more complex than I ever imagined. Because of an uncommon side effect associated with a different rotavirus vaccine, a large-scale safety and efficacy trial of nearly 70,000 6- to 12-week-old infants was required. And while the large study was enrolling, miracles happened. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was born, and rotavirus was one of the two investigational vaccine candidates first targeted for accelerated introduction into low-income countries. Currently, there are four rotavirus vaccines that have been prequalified by the World Health Organization recommended for all children everywhere. Rotavirus vaccines have been introduced in over 100 countries. And rotavirus diarrheal disease deaths have been cut in half—from 500,0000 to an estimated 250,000 annually.

What is the greatest challenge you have faced in your career?

We at the Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute are charged with taking on some of the world’s most lethal diseases: tuberculosis (TB), malaria, enteric and diarrheal diseases, and conditions affecting maternal, newborn, and child health. We are confident that we can realize our goals, but we also know it won’t be easy. These diseases disproportionately affect the poor. Product development at baseline is enormously complex and this complexity is amplified manyfold for our disease areas of interest. The pathogens causing TB and malaria have complex lifecycles. We don’t understand the immunologic mechanisms that protect against infection and severe illness. Clinical studies must be done to evaluate whether new interventions can treat or prevent these diseases in areas where the diseases are highly prevalent, which are some of the poorest in the world with little infrastructure for conducting research. Market forces don’t work in our favor. Our goal is to develop effective, safe, tolerable products to meet the needs of patients on the ground. And we believe firmly that we can realize our goal by applying tip-of-the-spear science, top talent, and committed financing to these diseases that have consistently cut short the lives of millions year after year around the globe.

Describe a specific project or situation that has had a profound impact on you to this day.

On a spring morning in 1999, I found myself in a pediatric clinic in Kisumu, Kenya—a single room in a concrete block building on the hospital grounds. The waiting area was outside–concrete benches protected from the rain by a tin roof. The mothers would line up on the benches holding their babies waiting to be called—usually 20 to 30 mothers on any given morning. This particular morning was hectic. Three mothers were pressing their way into the door of the clinic wanting their babies to be seen right away.

One of the mothers caught my eye. She was holding her baby boy, who looked to be about a month old. He had severe diarrhea—she had just loosely folded a diaper around his little bottom to contain it as best she could. He was very dehydrated—his skin was dry; his eyes were sunken. His mother was frantic trying to get him to nurse, but he was so sick his mouth was too weak to latch on. And then this mother seemed to change her mind, backing out of the doorway and stepping off to the side of the building. I followed—her baby needed care; he was at great risk of dying. She had a rag in her free hand, and as I watched, she stooped down, dipped that rag into a mud puddle and squeezed drops of water from the rag into her baby’s mouth desperately trying to save him. Deeply entrenched extreme poverty in this region left few options for this mother and her infant—as it does in many parts of the world. No mother should ever have to go through that.

Seven years later I had the incredible opportunity to return to the very same place to set up studies of the rotavirus diarrhea vaccine. And now nearly two decades later, working with partners and colleagues at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, I have had the opportunity to support the development of an entire portfolio of vaccines against diarrhea. For me personally, this is very full circle. For mothers and fathers living in poverty, the successes we have as a biotech organization will mean their children will not suffer needlessly from diseases we will be able to prevent and treat. Every child, every person deserves the chance to live a healthy, productive life.

Who has had the greatest impact on your professional career development? What inspired you to work in the field of infectious diseases?

I have been fascinated with infectious diseases and “germs” since childhood. I think this stems from my father’s experience with tuberculosis two years before my birth. He worried that the disease would “reactivate,” and he would transmit it to my siblings and me. He told me stories of this “germ” that was asleep in his lungs that could wake up at any time. While perhaps I should have been frightened of catching this “bug,” I was mostly fascinated. This fascination turned into a passion that grew throughout my undergraduate and medical school training and led me to a fellowship and career in infectious diseases.

I have been fascinated with infectious diseases and “germs” since childhood. I think this stems from my father’s experience with tuberculosis two years before my birth. He worried that the disease would “reactivate,” and he would transmit it to my siblings and me. He told me stories of this “germ” that was asleep in his lungs that could wake up at any time. While perhaps I should have been frightened of catching this “bug,” I was mostly fascinated. This fascination turned into a passion that grew throughout my undergraduate and medical school training and led me to a fellowship and career in infectious diseases.

I have many people to thank for their tremendous support of my career. My seventh-grade science teacher, Barbara Howell, taught me the importance of conducting blinded, controlled trials by using Life Saver candies for which the color and flavor didn’t match (e.g., the purple candy was lemon-flavored). Dr. Lazlo Maak, the director of the clinical laboratory in which I did my undergrad training, believed in me and helped me understand what was needed to go to medical school. Dr. Gary Marshall secured funding, started a fellowship program, and accepted me as the first fellow—literally a miracle for me given that my mother had been recently diagnosed with ALS and I needed to be near her. Dr. Joseph Heyse was responsible for the design of the large-scale Rotavirus Safety and Efficacy Trial (REST) by translating my clinical intuition into statistical criteria; he remained a mentor and friend until his passing. Dr. Paul Offit, the inventor of RotaTeq with Drs. Fred Clark and Stanley Plotkin, patiently taught me the science of rotavirus and vaccines, encouraged and supported me when others doubted the program, and has remained a lifelong friend. Dr. Adel Mahmoud, through his championship of the rotavirus vaccine program at Merck when others were dubious, taught me the importance of following my North Star and of advocating for those less fortunate. And many, many more …

Who do you most admire, and why?

Leonardo DaVinci, a true polymath. I am fascinated by the innovation that happens when experts from different disciplines intersect. Da Vinci displayed this phenomenon—a scientist, artist, engineer, inventor—and the “intersection” was contained within him. Each of us experience his influence every single day in so many aspects of our lives—from contact lenses to robotic surgical systems. He must have been a time traveler. I also love his human side. He overcame incredible odds beginning with his illegitimate birth, educating himself, and finding unique ways to pursue his research. The last journal entry before his death is especially poignant: “The soup is getting cold.” While scholars have looked for deep meaning in this sentence, most agree—he realized it was time to finish his work for the night and have dinner—as hard for him as it can be for anyone who loves their work.

Recognizing the challenges that we face, both as a nation and as a global community, what are the greatest threats and opportunities for the infectious disease profession?

Since I was first asked this question in January 2020, the few reported cases of novel coronavirus have evolved into a full-blown pandemic. What most keeps me up at night is thinking about the current and the next pandemic. While we have made significant scientific gains in understanding COVID-19—perhaps at a rate faster than any other time in history—as an infectious disease doctor it frightens me how many unknowns remain about its transmission, pathogenesis, unpredictable symptomology, and course of disease. What’s more, our focus on controlling the current epidemic has obscured to some extent our need to build stronger systems and policies for pandemic preparedness that allow us to remain agile in the face of the unknown. If there is anything stable about the history of infectious diseases, it is that we will always be vulnerable to new outbreaks. We were and are woefully unprepared—the political will to support the infrastructure needed to address a pandemic grows with each outbreak but also unfortunately wanes after it is over.

However, aspects of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic bring renewed hope. One example is The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, a groundbreaking global collaboration including governments, scientists, businesses, civil society, philanthropists and global health organizations intended to accelerate development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. As of September 2020, over 170 countries are engaged in COVAX, the vaccines pillar of the ACT Accelerator, to ensure COVID-19 vaccines are available worldwide to both higher-income and lower-income countries. We must find a way to sustain this political will in “peace time” to support sufficient pandemic preparedness globally and never again experience the health and economic tragedy that we have experienced with COVID-19.

There is also antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—whether it be Candida auris in the US, multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB in South Africa, or extensively-drug-resistant (XDR) Salmonella Typhi in Pakistan. A multifactorial response is needed—incentives for development of new antimicrobials, incentives not to overutilize those antimicrobials once they are created, and vaccines to prevent these diseases in the first place. How can we catalyze the political will and systems strengthening essential to address AMR given the complacency of generations that have long forgotten the death and devastation of the pre-antibiotic era?

These threats are only amplified by climate change, which is altering our ecosystems and supporting emergence of new diseases. Among infectious diseases, water- and foodborne diseases and vector-borne diseases are two main categories that are forecast to be most affected. Expansion of infested mosquito areas will increase vector-borne infectious diseases such as malaria and dengue and expand the areas defined as “epidemic.” Food and water will be at higher risk of bacterial contamination. And general decline in economic and social conditions will also contribute to the higher risk of infectious diseases. It’s inspiring to see citizens of the world rallying, setting ambitious goals for solving it. Infectious diseases professionals have an important role to play in developing and implementing practical ways to reach those goals, addressing the health inequities that climate change brings.

What are the greatest changes you have seen in the profession since you began your career?

One afternoon during my final year of medical school, the infectious diseases attending on call paged me and said, “Come to the ER. There is a child with Hib sepsis. This may be the last case you will ever see.” He was right—the year was 1990 and I didn’t see another case of Haemophilus influenzae type b sepsis until more than 20 years later—and that was in a hospital in rural India in a child who had not received the Hib vaccine. Numerous other vaccine-preventable diseases have all but disappeared during my career—“flesh-eating bacteria” associated with chickenpox, deafness from pneumococcal meningitis, and amputation of limbs from meningococcal sepsis. The number of children under 5 years of age who die each year from rotavirus gastroenteritis has been cut in half from 500,000 to 250,000 children globally. Now I dream … in the early 1900s, 20,000 deaths were caused by tuberculosis (TB) in the US; by 2017 the number of TB deaths in the US dropped to 520. Yet, in low- and middle-income countries, approximately 1.6 million people still die from TB each year. And in these countries, TB is a disease not of the elderly, but of young adults during the prime of their lives. Progress in rich countries is laudable and it demonstrates that public health measures are effective.

How can we make the same progress in low-resource settings?

Knowing what you know now, what, if anything, would you do differently in your professional life?

I use what I learned from each stage of my training and career every day. I could have just focused on pediatrics in residency and avoided internal medicine. But then would I have understood how TB strikes young and mid-adults in their prime? I could have combined my CDC EIS and University of Louisville infectious diseases fellowship into one. But then would I have the firsthand experience of pneumococcal, meningococcal, and rotavirus disease, appreciate a world without them, and want the same extinction of other infectious diseases? I could have left the private sector earlier and joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. But then would I have had the experience that is needed to accelerate development of interventional products for low-income countries? My mentors, my patients, and my experiences have shaped who I am today. I am grateful and so fortunate that my career has evolved in ways that I could have never imagined—which leads me to conclude that I wouldn’t want to change a thing.

What most keeps you up at night?

We at the institute are blessed with funding and human and technical resources to pursue and develop drugs, vaccines, antibodies, and other measures on our own and through collaborations to address vexing conditions that affect vulnerable populations. Drug and vaccine development timelines are long, full of risk and complexity, and demand excellence at every step of the way. I worry about the institute leveraging this extraordinary opportunity to bring important treatment options to all the people who desperately need them. We could potentially reset a future for many, many people. If a few things go right, some of our programs could change the course of human history. Are we sufficiently delivering on that responsibility?

What advice do you have to offer to the next generation of infectious disease professionals?

First, follow what you love. It is important to seek out what ignites your passion, what you love learning about, and what will help you get out of bed every morning. This does not mean that you will love every project, role, or job. You will have to take on things that may not fit your preferences perfectly—or that you are just unsure about. Take advantage of those opportunities to learn and experience new things.

Second, work across disciplines. In the infectious disease community, we are faced with complex, contemporary challenges: a need to question our own assumption that antibiotics will always be there when we need them, and a need to address a minority ideology that vaccines are optional because the diseases they prevent are gone. Addressing these challenges requires a large community of experts from many different arenas—psychologists, economists, social media experts, and communication experts to name a few. Working across these disciplines will be essential to solve the multi-faceted challenges that fall squarely within the responsibility of the infectious disease professional.

Third, identify your North Star and stay true to it. As the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us, the scientifically robust recommendations of infectious diseases physicians may be unpopular and even a target of criticism. On the flip side, the pandemic has also taught us that health care professionals combatting infectious diseases can be—and are—heroes. Whether it’s your time to be the target or your time to be the hero, accept both roles with honor. And stay true to the vision of a healthier future free from the threat of infectious diseases.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

“It all matters. That someone turns out the lamp, picks up the windblown wrappers, says hello to the invalid, pays at the unattended lot, listens to the repeated tale, folds the abandoned laundry, plays the game fairly, tells the story honestly, acknowledges help, gives credit, says good neigh, resists temptation, wipes the counter, waits at the yellow, makes the bed, tips the maid, remembers the illness, congratulates the victor, accepts the consequences, takes a stand, steps up, offers a hand, goes first, goes last, chooses the small portion, teaches the child, tends to the dying, comforts the grieving, removes the splinter, wipes the tear, directs the lost, touches the lonely, is the whole thing. What is most beautiful is least acknowledged.”—We Are Called to Rise by Laura McBride