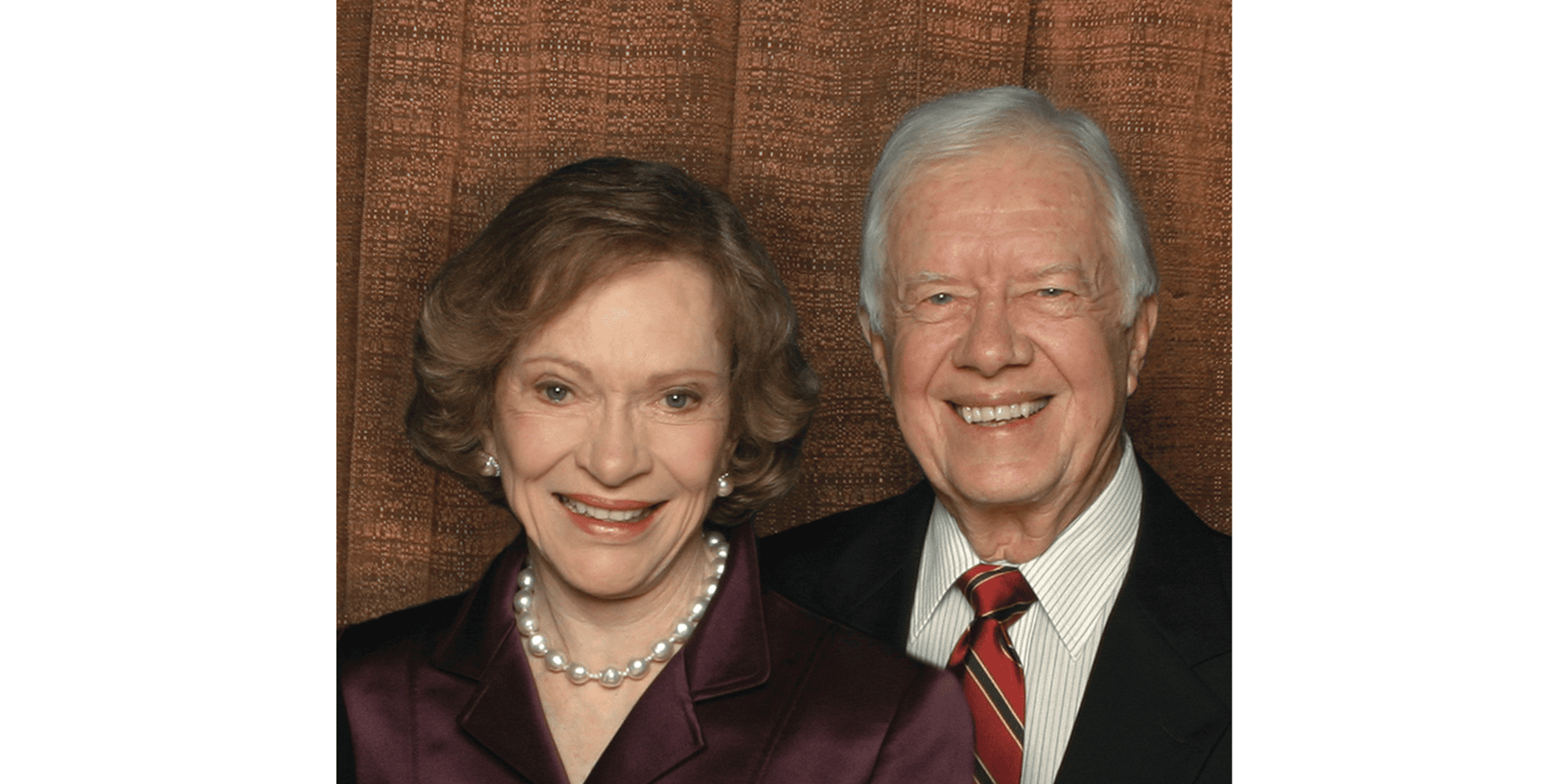

The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award honors individuals whose outstanding humanitarian efforts and achievements have contributed significantly to improving global public health.

Seth F. Berkley, MD, of the Pandemic Center of Brown University, received the 2024 Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award in recognition of his work as a global health pioneer and a champion of equitable access to vaccines.

A physician and infectious disease epidemiologist, Berkley led Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance for 12 years, raising $33.3 billion and increasing coverage of routine immunization in lower-income countries. Gavi has vaccinated more than 1 billion children and introduced more than 600 new vaccines, reducing vaccine-preventable child deaths by 70%, and preventing more than 19.9 million deaths. While at Gavi, he co-created COVAX, a global multilateral solution that worked with partners and leaders of 193 economies to secure, ship, and help deliver nearly 2 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine to 146 economies. He previously founded the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) to develop an AIDS vaccine for developing countries. “Seth Berkley restlessly takes on and delivers on big challenges,” said Bruce G. Gellin, MD, MPH, in nominating Berkley. “Turning vaccines into vaccinations among the most vulnerable and ensuring that routine immunizations were indeed routine, he also played a pivotal role in changing the way the world prevents and responds to global health crises and epidemics.”

Tribute Video

Acceptance Speech

An Interview with Seth Berkley

What is your greatest professional accomplishment or challenge?

I founded several great organizations: The International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), the HIV/AIDS Alliance and of course, the important work of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance in vaccinating more than 50% of the world’s children. But I would have to say setting up COVAX during a pandemic lockdown and delivering more than 2 billion doses of vaccine to 146 countries in the largest and fastest rollout in history, is probably my greatest professional accomplishment. The greatest challenge was attempting to provide vaccine equity through COVAX despite intense vaccine nationalism, vaccine diplomacy, and bad behaviors of countries, companies, and politicians.

Describe a situation that has had a profound impact on you to this day

In 1985, I traveled by camel through the restricted security zone of the Darfur region of Sudan to ultimately document one of the worst famines in history—93% moderate to severe malnutrition in children. But it was the measles infections that would sweep through the camps and the rows of small graves that I cannot forget.

Who or what inspired you to work in infectious diseases?

I had 3 major mentors: Bill Foege (a key figure in the eradication of smallpox), who is a hero to all of us in public health. I watched how he forged a strong partnership at the Task Force for Child Survival, managing some very big egos. He sent me to Uganda to help improve immunization after the difficult times of Idi Amin and Milton Obote, but also allowed me to help with the terrible outbreak of HIV/AIDS. Stan Aronson, who was the founding dean at Brown Medical School, supported my education and engagement in tropical medicine and also sent me to Jackson, MS to work with Robert Smith, an amazing family practitioner and iconic civil rights physician who taught me about overcoming adversity.

I chose infectious diseases as a specialty because it was where I thought I could make the most difference in terms of public health outcomes and equity.

Who do you most admire, and why?

Bill Foege, best public health speaker and storyteller I know. His ability to use humor and humanism to get people to work together as he did in the Task Force for Child Survival was a lesson for the work I did across my life.

What are the greatest threats and opportunities for the profession?

It is the best of times, it is the worst of times. Infectious diseases have been the main killer of people throughout human history. Through vaccines, sanitation, and antimicrobial agents, we have reduced that burden dramatically and doubled life expectancy. But today, we need to deal with the challenges from our own success: Increased risks of outbreaks and pandemics due to urbanization, migration, population growth, and climate change, but also antimicrobial resistance from the misuse of antibiotics. We need investment in new vaccines and antibiotics, and pandemic prevention and preparedness are not where they need to be.

What are the greatest changes you have seen since you began your career?

The greatest change is the amazing advancement in science: molecular biology, gene editing, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI). In the vaccine space, we have gone from empirical vaccinology to recombinant DNA, to reverse vaccinology, and now structural vaccinology using synthetic biology. On the delivery side, in the US there has been a trend toward for-profit medicine with increased spending, physicians shifting to paid staff with health outcome indices, decreases in health equity, and profit flowing more and more to middlemen who do nothing to improve the health of the population. This is not a sustainable model.

Knowing what you know now, what, if anything, would you do differently?

I loved the arc of my career. I should have pivoted to pandemic preparedness even earlier than I did.

What is your advice for the next generation of infectious disease professionals?

There was a famous urban legend that Surgeon General William Stewart said, “It’s time to close the books on infectious disease, declare the war against pestilence won, and shift national resources to such chronic problems as cancer and heart disease.” Not only did he never say that, but it is also completely wrong. We continue to be in an evolutionary war with microbes. As the population ages and our ability to adjust the immune system to treat cancers and autoimmune disease grows, the roles of infectious disease professionals only become more important (and dare I say, interesting).

My personal motto in life: Live like you are going to die tomorrow, learn as though you are going to live forever.

For additional perspectives from Seth F. Berkley, MD, listen to the NFID Infectious IDeas podcast, A Leader for Global Health Equity.