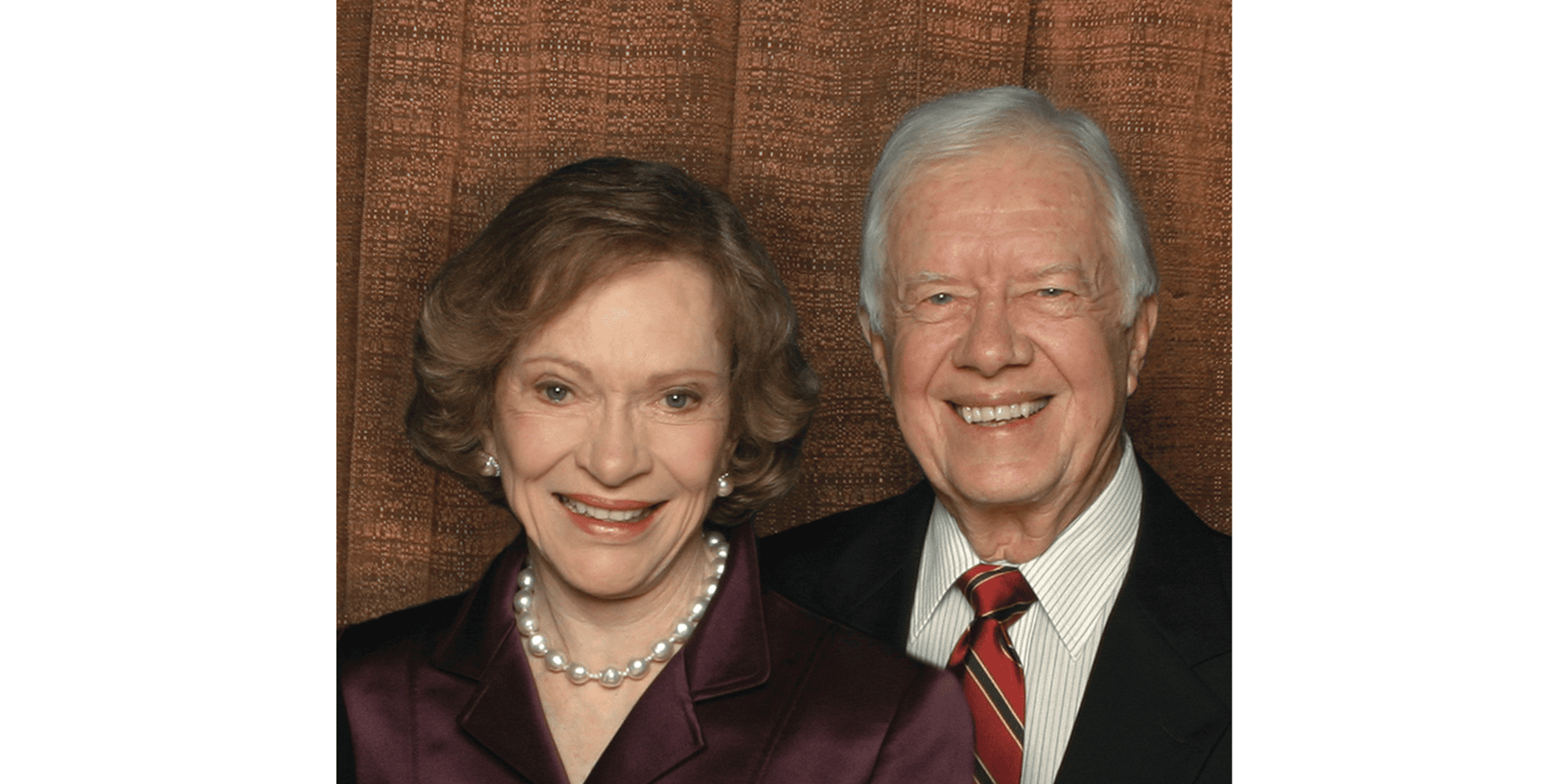

The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award honors individuals whose outstanding humanitarian efforts and achievements have contributed significantly to improving global public health.

Katherine L. O’Brien, MD, MPH, director of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals at the World Health Organization (WHO), has been selected to receive the 2022 Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award in recognition of her achievements as an international leader in vaccinology and a tireless champion for global vaccine equity. In her role at WHO, she has provided outstanding leadership in shaping the COVID-19 vaccine global strategy.

Through guiding the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), she helped to develop new policies for 10 separate COVID-19 vaccines, while being a major voice for equitable vaccine access in low- and middle-income countries. Renowned for her ground-breaking research, Dr. O’Brien was one of the first investigators to quantify the global burden of pneumococcal disease, its serotypes, and define the relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and acquisition of disease, unlocking the case for pneumococcal vaccine use globally. Her contributions to decision-making and policy development by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance have enabled millions of children throughout the world to not only have access to life-saving, affordable pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, but also vaccines against HPV, polio, COVID-19, and soon malaria. Dr. O’Brien’s extraordinary leadership has been evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where she has tirelessly advocated and worked for vaccine equity. Her contributions to COVAX helped lead to the remarkable achievement of delivering more than 1 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine to the world’s poorest countries.

Tribute Video

Acceptance Speech

An Interview with Kate O’Brien

What is your greatest professional accomplishment?

Working on bringing pneumococcal conjugate vaccines all the way from investigational products, establishing their value proposition, through to policy positions, global funding decisions, country decision-making, introduction, and optimization has been enormously gratifying. I’ve also worked on these same steps for other new, life-saving vaccines, which has led to them becoming part of the Gavi-supported portfolio—including malaria and rotavirus vaccines, holding the promise of saving millions of lives.

It is hard not to also reflect on the COVID-19 pandemic and the leadership work I have been privileged to be part of in bringing these vaccines to individuals, families, communities, and countries around the world. Through COVAX, I’ve been deeply involved in establishing a vaccine portfolio and investment case, formulating vaccine policies, allocating highly constrained supply in a fair and equitable way, establishing the world’s only international no-fault compensation scheme, supporting countries on their readiness to implement the vaccines to get shots into arms.

Outside the vaccine field, I led an outbreak investigation of deaths from acute renal failure among young children in Haiti, which led to the deaths of more than 100 children. It turned out to be caused by diethylene glycol poisoning, which came from contaminated, locally manufactured acetaminophen syrup. The product was immediately removed from the market which stopped the outbreak. Although not on the scale of lives saved by vaccines, figuring out what was causing the rapidly escalating epidemic of deaths, and taking decisive action to halt the outbreak was really meaningful.

What is the greatest challenge you have faced in your career?

The politicization of science and public health has at times overtaken evidence and independent policy decision-making—this challenge has grown substantially. Vaccine nationalism and corporate profit motivations have driven decisions that are at odds with vaccine access, equity, and public health impact.

Describe a specific project or situation that has had a profound impact on you to this day.

My first job out of residency was as a physician on a pediatric ward at a hospital in Cite Soleil, a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Approximately 20-30 percent of children admitted to the ward would die—most of whom had preventable or treatable illnesses, such as measles, neonatal tetanus, meningitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, parasites, typhoid, diarrhea, malnutrition, and HIV. I felt powerless in the face of economic, social, and health system realities that could not provide for or protect the future of these children.

Who has had the greatest impact on your professional career development? What inspired you to work in the field of infectious diseases?

I have had the luck and privilege of being supported by inspiring, generous, and impactful mentors and colleagues throughout my education and career. Mathu Santosham, MD, MPH has been my career-long mentor, who I first met in 1988 as a pediatric intern. I have had so many fabulous colleagues who started out as supervisors, peers, co-trainees, or collaborators and have become treasured life-long friends—Anne Schuchat, David Goldblatt, Orin Levine, Maria Knoll, George Siber, Laura Hammitt, Shabir Madhi, Cyndy Whitney, David Murdoch, Anthony Scott, Kathy Neuzil, Marc Lipsitch, Neal Halsey, Andy Ruff, Ruth Karron—and many more.

I was inspired to work in the field of infectious disease for three main reasons:

- These diseases are preventable (or treatable)—in other words, the aspiration of the work in the field is driven by the fact that these problems can be solved! And solved well within the lifetime of a career. It was a field where you could see progress, you could work on going from the science and evidence to actual implementation. Population impact.

- The breadth and diversity of the issues include not only deep and wide science—microbiology, epidemiology, basic science, product development, clinical trials, and modeling—but also policy, financing, access, political decision-making for implementation and impact, program optimization, community engagement, confidence, and demand. Infectious diseases is a field that is profoundly about bringing evidence and data to create influence, with the immediacy of saving lives.

- It is a field that has no borders—I have always had enormous curiosity about the world around us all, and this was a field that gave me a way to experience and explore that world.

Who do you most admire, and why?

This is an impossible question to answer if I must choose one person I most admire. There are simply too many.

Right now, I most admire the young people around the world who are unafraid to call out, live out, create, and demand the change needed for climate justice and climate action. They are doing this with courage, fierce clarity, and a commitment to truth and science, in the face of deeply entrenched social, political, financial, and establishment positions that are resisting the changes needed to allow for a livable future. Our western culture, our generation, and those before us failed to confront the existential threat we created, and we have repeatedly failed to act. I am incredibly inspired by those who are speaking truth to power and committing themselves and their futures to the change that has to come.

Recognizing the challenges that we face, both as a nation and as a global community, what are the greatest threats and opportunities for the infectious disease profession?

Climate change and scientific denialism are the two greatest threats I see facing us all right now, not only for the ID world but also for our societies and humanity.

The opportunities are fundamentally about scientific openness, collaboration, sharing of evidence, and a commitment by the scientific world to communication, advocacy, and relentless prioritization of truth even in the face of political and social resistance.

What are the greatest changes you have seen in the profession since you began your career?

Globalization of opportunity has expanded enormously over my career. There are so many more research institutions and groups working in global health and vaccines in particular.

We are also now finally seeing the de-colonialization of science and global health especially with the founding and development of regional and national institutions throughout the world, particularly on the African continent. This is incredibly welcome and will further expand the breadth of opportunity to people in the very places where the most critical science is needed.

Expansion of funding and institutions particularly for infectious disease work and vaccines is very different now compared with when I first started in this field (Gavi, CEPI, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Africa CDC, International Vaccine Institute, and others). With budgets under significant strain, the big question will be: How will this align to make even more impactful progress, or will it not align well and become increasingly fragmented?

But also, the loss of public institution strength in the development of vaccines. We now have clinical product development for vaccines largely driven by manufacturers and have lost the independence of institutions that used to drive the science of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. We no longer have investigator-driven product development protocols, but instead have protocols driven by the manufacturers with multi-site, multi-investigator trials, which means a lack of independent, unbiased development. It also means we have lost the means by which to address critical policy questions if they are not aligned with the interests of an individual manufacturer.

Knowing what you know now, what, if anything, would you do differently in your professional life? Any regrets?

My regret is to not have been one of those people who can live on 4-5 hours of sleep a night!

If I had this to do all over again, I would have worked for more extended periods in country at the field level and to have done more learning outside my specific area of work. Finding that time to go outside of our areas of responsibility is important.

If I could have done anything else and waved a magic wand, knowing what I know now, I would have wished for the position, knowledge, and influence to take action on climate change a decade or two ago.

What most keeps you up at night?

Deep division in our societies around the world—we are not able to see the humanity in each other and the fact that the human species is a social and dependent species. We need each other.

Social media has many benefits, but it is also deeply contributing to the erosion and destruction of our collective consciousness. The generations that have grown up with the internet and social media are forced to live in ways that are not aligned with our human consciousness.

I think about the lack of courage of our political leaders to bite into the lemon and speak truthfully about what we need to do for the benefit and health of our societies. Our communities are made of people who want the same thing—peace, prosperity, meaning, and connection—and are human enough to accept the changes needed for a livable future, but they need leadership.

What advice do you have for the next generation of infectious disease professionals?

- Think big and start small … but start!

- The ‘p’ in public health is actually for ‘politics.’

Is there anything else you would like to emphasize or share?

- Family always comes first. There is nobody else who can be who you are to your family, but there is always someone at work who can step in for you when needed. Be sure your partner, your children, and your family know that there is nothing you hold more precious than them.

- Nothing happens without people, and nothing lasts without institutions. Surround yourself with those whom you admire and trust. Make your best contributions to the institutions you are part of, because institutions all have personalities and they are ultimately formed and shaped by the individuals who create them, day in and day out.

- Be kinder than necessary, always. As Maya Angelou said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

- The opposite of poverty is not wealth, but justice.