The Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award is presented annually by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID) to honor individuals whose outstanding humanitarian efforts and achievements have contributed significantly to improving global public health through domestic and/or international activities.

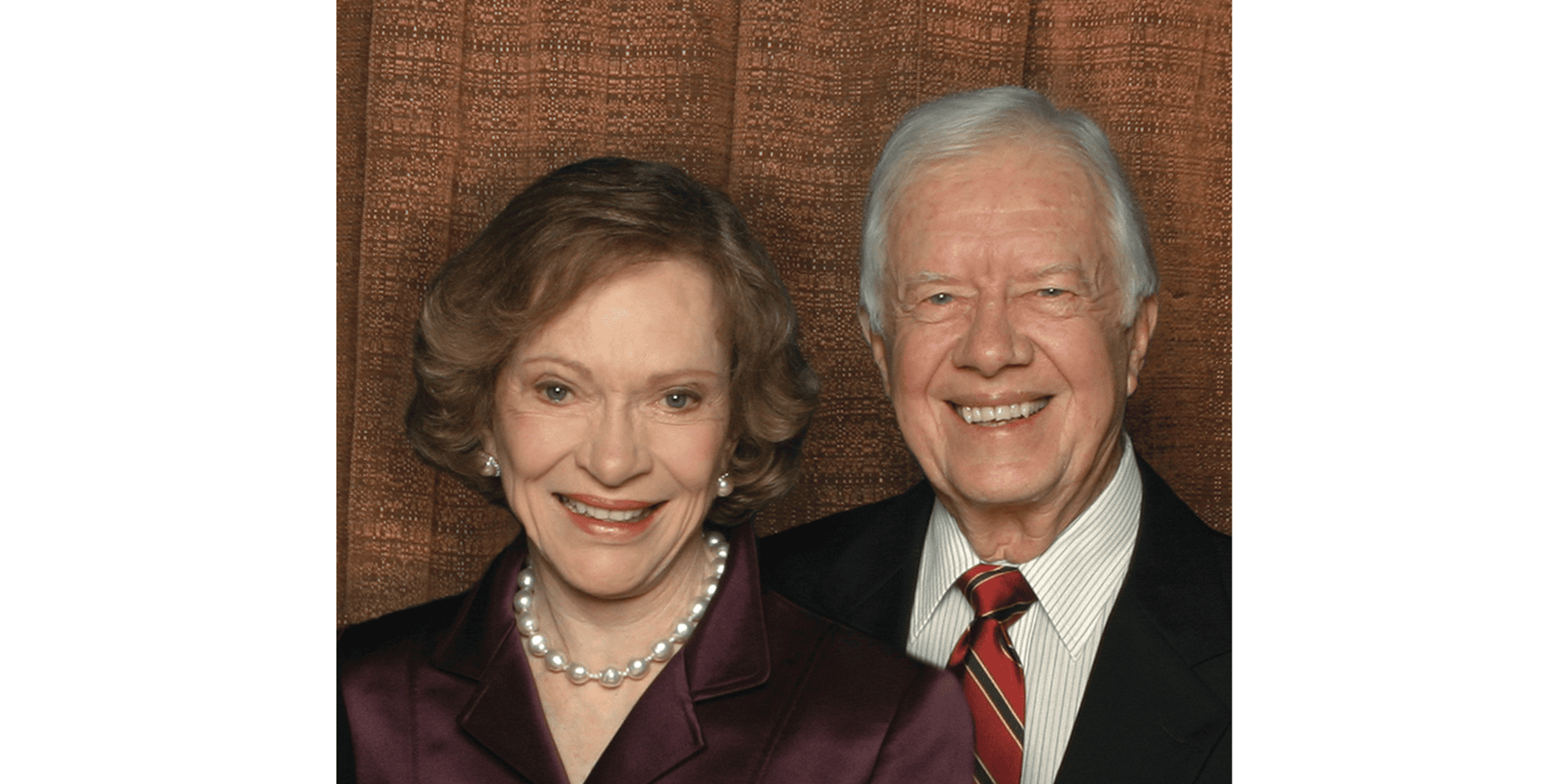

Established in 1997, the award is named for former President Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, who as outstanding humanitarians, have worked tirelessly to improve the quality of life for people worldwide. Through their work at The Carter Center, they have worked to resolve conflict peacefully, promote democracy, protect human rights, and prevent and eradicate disease. In recognition of their efforts, President and Mrs. Carter were presented with the first Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award in 1997.

NFID selected Anita K.M. Zaidi, MBBS, SM to receive the 2021 Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award in recognition of her outstanding humanitarian efforts and achievements that have contributed significantly to improving global health.

Currently director of Vaccine Development, Surveillance, and Enteric and Diarrheal Diseases, and president of Gender Equality at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Dr. Zaidi has dedicated her career to vaccine development and disease prevention in the poorest parts of the world. She led the strategy for typhoid conjugate vaccines, oral cholera vaccine stockpile enhancement, and development of the first low-cost rotavirus vaccine by a developing country manufacturer. She currently co-leads the program for novel coronavirus vaccines at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Her prior work on newborn health and vaccination in the poverty-stricken fishing communities of Karachi is credited with reducing child mortality by an estimated 65 percent.

An Interview with Anita Zaidi

What is your greatest professional accomplishment?

Working with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and our partners on the development and introduction of the typhoid conjugate vaccine in low- and low-middle income countries has been my greatest professional accomplishment. For too long, this disease—which invariably affects the world’s poorest people—was neglected. It was a great honor to be involved in my role as director of Enteric and Diarrheal Diseases and Vaccine Development for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

What is the greatest challenge you have faced in your career?

Gaining the confidence to pursue my goals. I think a lot of young women can relate to the struggle I faced starting my career in Pakistan. As a woman, it can be difficult to instill the confidence in yourself that you can be successful through persevering and overcoming societal barriers.

I’ve found that the road to professional growth is not linear for many women. The childcare burden is still a big issue for women all over the world. In the US, it was very difficult to raise my daughter—childcare was unaffordable while I was a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases and my husband was pursuing residency training. That situation has not changed in more than 25 years. We should not leave this problem for women to solve. Investing in childcare should be thought of as investing in critically essential infrastructure such as roads and schools so women can realize their full potential.

Describe a specific project or situation that has had a profound impact on you to this day

I really enjoyed the community health rotations that were a requirement of our curriculum at the Aga Khan University, and I had a very formative year working in diarrheal disease research in the northern areas of Pakistan after graduation. I moved on to specialized clinical training in the US with the goal of becoming a pediatrician scientist. Mid-career, when I was at a crossroads on what type of work to pursue, I had a chance meeting with a senior pediatric professor and department chair at an academic conference. She said, “Don’t be afraid of taking on new things and trying out new ways of thinking that are more relevant to the problems you are seeing around you.” This was a turning point that led me to where I am today.

I changed my career focus to community work with the goal of trying to solve big infectious disease challenges affecting child survival. Because of my training in a laboratory, this was especially daunting. You can’t control all the variables in your community work the way you do in a lab. But I could see an enormous opportunity to make a difference. That risk I took to do community work ended up working out and now, I apply my science training to all the work that I do. It has become a theme across my entire career: asking how we can bring lab science and an evidence-based mindset to solve the biggest problems that poor people face.

Who has had the greatest impact on your professional career development and what inspired you to work in the field of infectious diseases?

Someone who had a tremendous influence early in my career was Claire Panosian, a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She was a visiting professor when I was a medical student at the Aga Khan University. At the time, I didn’t realize you could become an infectious disease physician. She invited me to come to the US to do an infectious disease elective at UCLA and stay at her house—that was the first time I had ever been to the US.

This role had me working with patients who had HIV/AIDS, and in those days, there was no therapy. The most we could do was provide palliative care. I learned then that when you are working with infectious diseases, it is not just about how the disease affects the patient but also about the larger social determinants that cause disease. These are universal themes regardless of where you are born. That role was an influential time in my career development, and I’ve kept up with Claire over the years.

I am also very grateful for all the opportunities provided by the Aga Khan University during my student days, my time as a faculty member, and the recognition I received for my research.

Who do you most admire, and why?

I really admire Malala Yousafzai for her courage and dedication to the education of women and girls. She continues this important work despite all the things that have happened to her and I really admire that.

I also admire my mother. She overcame daunting challenges and a conservative upbringing to go to medical college in Pakistan and become the most educated person in her family. She continued her work as a pediatrician while raising five daughters, and she has been a mentor to so many people to this day.

Recognizing the challenges that we face, both as a nation and as a global community, what are the greatest threats and opportunities for the infectious disease profession?

The biggest threat is not recognizing that tackling infectious diseases will require the whole world to work together. COVID-19 has shown us how we are not equipped as a global community to battle infectious diseases of this scale. Diseases don’t respect international boundaries. We need the world to come together to understand that if an infectious disease is a problem anywhere, the disease is a problem everywhere.

COVID-19 is an obvious example where we addressed a disease as a country-specific problem, and it quickly became a global problem. We can’t stop travel, so we cannot rely on boundaries to stop diseases. The opportunity I see is to work together and set up global prevention and response structures as we are doing with the climate change crisis. This means investing in public health infrastructure to enable prevention and early detection of infectious disease outbreaks in the poorest parts of the world. But also, in the richest. Lack of investment in public health has caused ancient diseases like syphilis to have a big resurgence in the US. There were almost 2,000 cases of congenital syphilis in the US in 2000!

What are the greatest changes you have seen in the profession since you began your career?

The biggest changes I’ve seen since I began my career were the introduction of effective HIV treatment and the disappearance of bacterial meningitis in children due to widespread use of Hib and pneumococcal vaccines. When I trained as a pediatric infectious disease fellow, most of my time was spent with children admitted with end-stages of HIV/AIDS. I had never seen anything like what these patients went through.

When highly active anti-retroviral therapy became available, the ID fellows that came after me had no inpatients with HIV/AIDS. In barely a year, we went from extremely sick inpatients to no patients with pediatric AIDS on the wards. And now that we know how to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, we hardly see any children with HIV and have very few cases globally. In my professional career, that has the most dramatic change.

Beyond that, there are so many new vaccines we just didn’t have before. Many devastating infectious diseases that we encountered in my early clinical career are virtually gone now that we can prevent them with vaccines, such as Hib and pneumococcal disease. When I was a student, we also didn’t have a way to get a new vaccine to children in developing countries. GAVI, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, which was co-founded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation along with other key donors, has made it possible for vaccines to be used to protect people around the world soon after they are developed. We now have solutions for many diseases that were not possible to prevent 30 years ago such as rotavirus diarrhea, the biggest diarrheal disease killer of children. We also have vaccines against cholera, typhoid, meningococcal meningitis, Hepatitis B, and newer polio vaccines.

Knowing what you know now, what, if anything, would you do differently in your professional life? Any regrets?

That’s a hard one. I’m such an optimistic, forward-looking, and solutions-oriented person that I don’t spend much time dwelling on the past. One has to stay open to learning from mistakes and continuously improving. I’ve certainly made mistakes and have learned from all of them. They usually have had to do with management of the inevitable conflict that arises in human interactions.

Many people questioned the seemingly irrational decision to go back to work in Pakistan in 2000 after spending 11 years in the US, but that has been a very rich and rewarding experience with tremendous lessons learned for the work I do today at the Gates Foundation, making innovation work for the poor and marginalized.

What most keeps you up at night?

The eradication of polio. We worked so hard to get to where we are today, and we need to solve this problem. We eliminated wild poliovirus type 2 and type 3 from the world, but there are two problems left: Pakistan and Afghanistan have not interrupted wild poliovirus type 1 transmission, and the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 outbreaks happening in many countries.

We have a limited window of time to solve these issues globally, and we have the solutions to both these problems. Of course, Pakistan is where I am from, so this problem is very close to my heart. I think we can get there with a little extra last-mile effort.

What advice do you have to offer to the next generation of infectious disease professionals?

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how very relevant infectious disease expertise, public health work, vaccine science, and research skills are today. I think it’s a very rewarding career. I would encourage many young professionals to explore it as a career option.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

I love the quote by the anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never believe that a few caring people can’t change the world. For indeed, that’s all who ever have.”