The John P. Utz Leadership Award honors individuals who exemplify and support NFID leadership goals, through service to NFID and/or the field of infectious diseases.

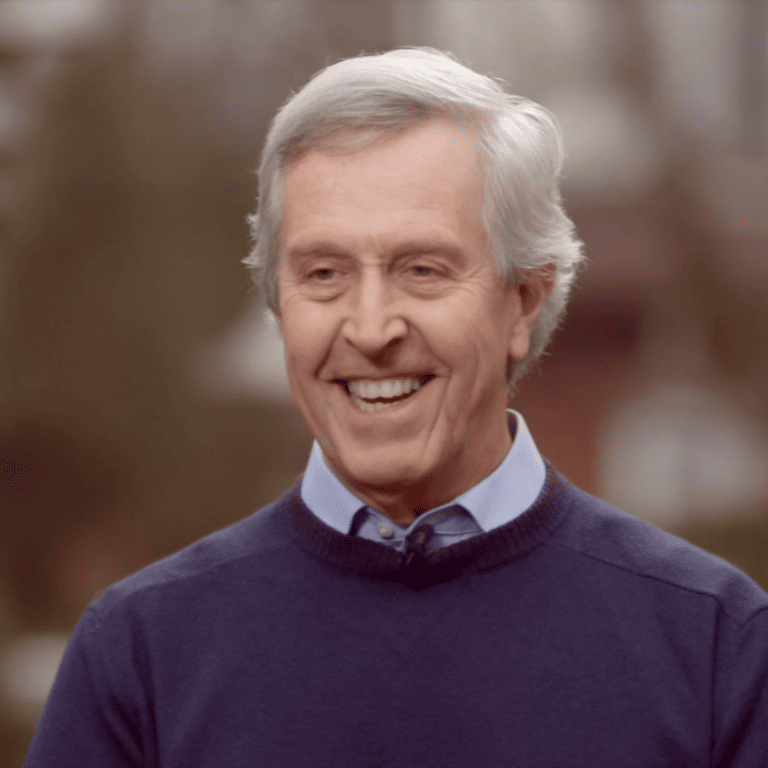

Bruce G. Gellin, MD, MPH, senior vice president at The Rockefeller Foundation and chief of global public health strategy for the Pandemic Prevention Institute, has been selected to receive the 2022 John P. Utz Leadership Award in recognition of his leadership and lifelong work to prevent infections through education, communication, and collaboration, as evidenced by his numerous national and international positions focusing on the reduction of infectious diseases through vaccination. Throughout his distinguished career, Dr. Gellin has held numerous positions leading and advising on global immunization, strategic policy development, and pandemic preparedness and response at national, multinational, non-governmental, and institutional organizations.

He has led key federal vaccine initiatives, including developing the National Vaccine Plan at the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and creating the first HHS pandemic influenza preparedness and response plan. Dr. Gellin has consulted as a technical expert to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and serves as a key advisor to the World Health Organization (WHO) on global immunization. His focus on vaccine demand as a public health issue both nationally and globally has made him a well-known champion of public health. He is a skilled immunization advocate through public policy, clear communication, and strategic planning and has made a distinguished impact worthy of this award.

Tribute Video

Acceptance Speech

An Interview with Bruce Gellin

What is your greatest professional accomplishment?

The project that tops the list was putting together the government’s first pandemic plan. When I joined HHS in 2002, the country had recently experienced 9/11 and anthrax attacks. The latter was a wake-up call on the importance of being prepared for a public health emergency with the necessary programs, tools (especially vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics), policies, and messages.

The HHS Secretary tasked me with developing the department’s first-ever pandemic influenza preparedness and response plan, which ultimately evolved into a whole-of-government effort to create the guidelines and systems needed to keep the country safe from an influenza pandemic—later expanded to include an all-hazards approach. It was clear then, and it remains obvious to all now given the COVID-19 experience, that a pandemic begins as a health problem, but health is just how it starts—as it can rapidly evolve and cause significant social, economic, and security disruptions at home and around the world.

What is the greatest challenge you have faced in your career?

The greatest challenge has been understanding how to translate evolving science into useful, actionable information that the public can trust and decision-makers can use to inform policy. The fog of war isn’t a new concept, but the problem is now further complicated by mis- and disinformation.

In 1998, I was a medical officer at the National Institutes of Health working on clinical vaccine research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which gave me a front-row seat to cutting-edge science and the promise of vaccines in the pipeline. In parallel, my wife, who was expecting at the time, joined a mom’s club where current and expectant mothers were asking pointed questions about vaccines, including why so many more were now required—as there were many more than they recalled from their childhood. “Did children really need all of these vaccines?” The contrast between my two worlds could not have been more striking. Literally night and day.

It turned out that the mom’s club was a focus group. A national survey of parents that I conducted with colleagues revealed that nearly 25 percent of parents of young children believed that children received more immunizations than are good for them—one of several findings that signaled a vaccine confidence problem. This inspired the creation of the National Network for Immunization Information, an effort by leading professional societies to help healthcare professionals better engage with their patients, the public, policymakers, and the media and provide them with up to date and scientifically accurate information on vaccines. This challenge clearly has not gone away.

Describe a specific project or situation that has had a profound impact on you to this day.

Gap years are common now, but they certainly were not when I was in medical school. But the offer to spend a year in the Philippines as a Henry Luce Foundation Scholar was too hard to refuse. Through this immersive program, the stark differences between high-tech, state-of-the-art medicine and the reality of health on the ground in a developing country could not have been clearer. From this, my big takeaway was the value and importance of prevention. And, as infectious diseases were a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, in retrospect a career focused on vaccines and vaccination seems inevitable.

Who or what inspired you to work in the field of infectious diseases?

My path was not a straight line. I can point to a few special people with whom I worked at the right place and at the right time—inflection-point mentors. Common to all, despite having met them at very different times in my life, was their ability to make me feel like I was the most important person to them and that they always had time for me—even when they didn’t. Ever since then, I have committed to extending that philosophy to others and paying it forward. The mentors:

Bert Kaplan, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina, introduced me to the field of public health, with an academic flavor. I am fortunate that he maintained an open-door policy, as I took more than full advantage of his open door even though I did not take any of his classes.

During my second year of medical school, I was paired with a medical anthropology graduate student named Lili Armstrong on a summer project to monitor tuberculosis (TB) drug compliance among recent immigrants in New York’s Chinatown—the very early days of directly observed therapy (DOT). She introduced me to her husband, Don Armstrong, the head of infectious diseases at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital, who would regularly join us on our mission (and for lunch) in Chinatown.

What struck me most was his curiosity about the illness coupled with his empathy for people with infectious diseases. In this setting, the connection between the plight of individuals and the health of the community has stayed with me since.

During my residency interviews amidst too many less-than-memorable tours of hospitals and clinics, I met Bill Schaffner at Vanderbilt. He latched on to my proclivity for prevention. I learned about his career path which had included both clinical and epidemiological responsibilities and had taken him from the hospital, to the Tennessee state health department, to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). His implicit message was “follow me.” Without realizing it, I did.

When David Rogers left the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and came to Cornell as an emeritus professor, he asked me to support him in his roles as head of the New York State AIDS Advisory Council and vice-chair of the President’s National Commission on AIDS. This meant helping to set New York state and national guidelines on AIDS policy and addressing controversial issues at the time including testing and the potential risk of transmission through breastfeeding, and extended to social issues including housing. All at the intersection of science, policy, and politics.

Finally, as a fellow at The Rockefeller Foundation in the early 1990s, I worked with Phil Russell, a retired two-star general, on the establishment of the Children’s Vaccine Initiative, a precursor to Gavi. The project’s global ambition was to immunize all children and introduce new vaccines for infectious diseases into global immunization programs. It also had the very aspirational dream of creating a single-dose multivalent vaccine that could be given early in life. One dose, good for everything, forever. Yes, aspirational.

Who do you most admire, and why?

Over the span of my not-so-linear career, I have looked up to many different influential figures across disciplines and industries. Two, however, stand out most:

Peter Piot, former director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, grew up in Belgium dreaming of adventure and helping the most vulnerable. His career in infectious diseases forged a path that made both dreams a reality. His consistent and urgent push to improve conditions for the most vulnerable is palpable in every conversation I have had with him. Of course, it is more than fitting that the title of his memoir is, “No Time to Lose.”

Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, is an activist with a fierce commitment to equity. Trained as a neurologist, serendipity and opportunity took him to Vietnam where he led the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City. Not the usual path to lead Wellcome, where equity and data are part of his everyday vocabulary. His vision of a better world is contagious.

Both Peter and Jeremy followed their passions and still do. Both have been successful influencers as they embody the extraordinary combination of scientific excellence, policy strategy, strong communication, and global advocacy to advance progress. It is no surprise that both have also been honored by NFID in the past with the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award.

Recognizing the challenges that we face, both as a nation and as a global community, what are the greatest threats and opportunities for the infectious disease profession?

Our greatest threat is complacency. Our national experience with COVID-19 has magnified this fact, and I am getting increasingly worried that complacency will worsen when the pandemic finally recedes and efforts to improve for the future dissipate. We need to break the cycle of panic and neglect where we tackle an issue until we think it has been adequately addressed and move on. That is not a recipe for a long-term solution.

What are the greatest changes you have seen in the profession since you began your career?

With COVID-19 as the notable exception, most who work on vaccine-preventable diseases have rarely, if ever, seen many of the diseases that vaccines were developed to prevent. We have often said glibly that vaccines have been the victims of their own success, but as we continue to make progress, we need to remember the seriousness of these diseases and their sequelae to those who are infected even if we do not see them every day.

Knowing what you know now, what, if anything, would you do differently in your professional life? Any regrets?

One thing I would have liked to do differently is to stay closer to the frontlines of both medicine and public health. There is nothing like firsthand experience. Being at the bedside of a patient or in a community grappling with an evolving outbreak is a reminder of the people who are affected. It is why we chose to work in this field. Being at 40,000 feet gives you a great bird’s eye view, but it makes it much harder to see the people you are looking out for.

What most keeps you up at night?

This has changed a lot with time and has been influenced most recently by hearing the dreams and aspirations of children and grandchildren. What keeps me up now is worrying about the future. I am an optimist and would like to believe that the path to progress is direct, but lately, I have worried that it might not be. For now, I take solace—and inspiration—in a speech President Obama gave several years ago, when commenting on a raft of daunting global challenges: “We have to reject the notion that we are suddenly gripped by forces that we cannot control. We’ve got to embrace the longer and more optimistic view of history and the part that we play in it.”

What advice do you have to offer to the next generation of infectious disease professionals?

Knowing the science is critical, but it is not enough. Science will change, and we will all need to keep our eyes open for these shifts. In medical school, we heard (not so jokingly) that “half of what you’ll learn will be shown to be either dead wrong or out of date within five years of your graduation; the trouble is that nobody can tell you which half—so the most important thing to learn is how to learn on your own.” Facts matter, but learning, and learning again, matters more.

Is there anything else you’d like to emphasize or share?

From that great philosopher and the original rapper, Muhammad Ali:

“Stay in college, get the knowledge.

Stay there until you are through.

If they can make penicillin out of moldy bread

they can sure make something of you!”