Special thanks to NFID Director Sara E. Cosgrove, MD, MS, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Department of Antimicrobial Stewardship, for this guest blog post for US Antibiotic Awareness Week, November 18-24, 2019, an annual observance to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate antibiotic use.

Special thanks to NFID Director Sara E. Cosgrove, MD, MS, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Department of Antimicrobial Stewardship, for this guest blog post for US Antibiotic Awareness Week, November 18-24, 2019, an annual observance to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate antibiotic use.

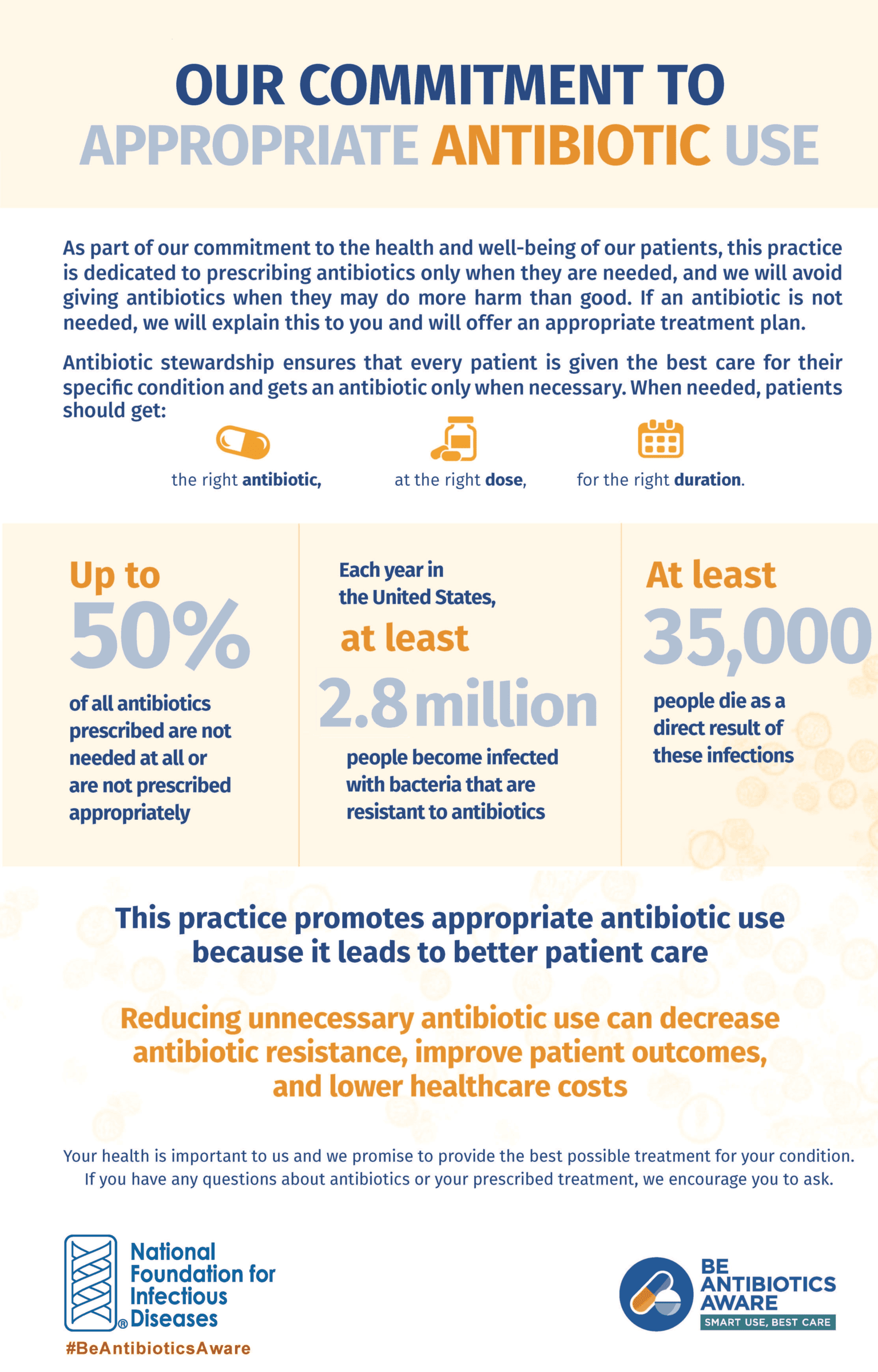

Every 11 seconds in the US, someone gets an antibiotic-resistant infection and every 15 minutes someone dies. That startling finding came from a new report, Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019, released last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Overall, CDC found that antibiotic-resistant infections cause more than 2.8 million illnesses and 35,000 deaths in the US each year.

As shocking as those numbers are, in my experience most people today will say that antibiotic resistance is a problem, but not one that affects them personally. The communications challenges around antibiotic resistance are similar to those of global warming. People do not expect their houses to be flooded, just as they do not expect to develop a drug-resistant infection.

For those of us who work in public health, the goal is to help people recognize that antibiotic resistance is not “someone else’s problem,” and to educate them about what they can do today to help prevent it.

There is still a perception among both prescribers and patients that antibiotics are only helpful and never harmful. Antibiotics have side effects, but some patients do not experience those side effects, and they cannot see the connection between the antibiotic and what’s happening to their gut microbiome. Further, some patients appear to benefit from antibiotics, when, in fact, their persistent cough after having a cold would have gone away in about the same amount of time even without the drug. All of this reinforces the misconceptions.

CDC estimates that at least 30 percent of antibiotics used in outpatient settings in the US are prescribed unnecessarily. Most of the ailments that send people to the doctor’s office are not life-threatening. The cough that you experience after you have a cold virus typically takes two to three weeks to go away and antibiotics don’t help. Even if you have sinusitis that might be caused by bacteria, that does not necessarily mean you need an antibiotic to get better.

CDC estimates that at least 30 percent of antibiotics used in outpatient settings in the US are prescribed unnecessarily. Most of the ailments that send people to the doctor’s office are not life-threatening. The cough that you experience after you have a cold virus typically takes two to three weeks to go away and antibiotics don’t help. Even if you have sinusitis that might be caused by bacteria, that does not necessarily mean you need an antibiotic to get better.

People think of antibiotic resistance as a population health-level issue. In fact, when you take an antibiotic, you may not know it, but resistance is happening to you. The human body is full of bacteria, so when you take an antibiotic there is a good chance that the “good” bacteria in your gut will become more resistant to that antibiotic. Some people won’t have consequences from this, but others will develop subsequent resistant infections or pass resistant bugs on to family members.

A study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) found that individuals who received an antibiotic for a respiratory or urinary infection developed bacterial resistance to that antibiotic. The researchers found that the effect was greatest in the month immediately after treatment, but lasted for up to a year.

I put these findings into practice not only in my role as an infectious disease physician, but also as a mom. My 15-year-old daughter has never had a single antibiotic. My 13-year-old son has had one dose.

I put these findings into practice not only in my role as an infectious disease physician, but also as a mom. My 15-year-old daughter has never had a single antibiotic. My 13-year-old son has had one dose.

Why? Because antibiotics are for serious infections—the kind that can land you in the hospital. When you take an antibiotic that you actually need, you feel miraculously better within hours. If that doesn’t describe how you felt the last time you took an antibiotic, then you may want to pause and think. Ask yourself (or your patients), why do you want an antibiotic? Are you willing to go one day longer with some discomfort if doing so could prevent future long-term health problems for yourself or a family member?

Here’s my advice for patients: Don’t walk into a clinic or doctor’s office with the intent of asking for an antibiotic. If you want to stay healthy, wash your hands, cover your cough, get plenty of sleep, and make sure everyone in your family gets vaccinated.

Pediatrician Rita Mangione-Smith, MD, MPH, and colleagues have developed the DART (Dialogue Around Respiratory Illness Treatment) program to improve communication and avoid unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. Her advice for healthcare professionals: Always end your conversations on a positive note: “The good news is, you don’t need an antibiotic.” To show your commitment to reducing antibiotic resistance through appropriate antibiotic use, take the NFID Antibiotic Stewardship Pledge.

Dr. Cosgrove will moderate a complimentary NFID webinar, Antibiotics May Not Be the Answer, on November 21, 2019 at 2PM ET. There is no fee to attend but pre-registration is required.

To join the conversation and get the latest news on infectious diseases, follow NFID on Twitter using the hashtag #BeAntibioticsAware; like us on Facebook; follow us on Instagram; join the NFID LinkedIn Group; and subscribe to receive future NFID Updates.

Related Posts

5 Things To Know about Antibiotic Resistance

There are steps everyone can take to help protect against drug-resistant infections

C. diff: An Urgent Public Health Threat

November is C. diff Awareness Month, an annual opportunity to raise awareness about this common but potentially deadly infection

A Perfect Storm: Antibiotic Resistance and COVID-19

COVID-19 disease caused surges in hospitalization with a proportion of patients experiencing severe disease that led to prolonged hospitalization and the use of invasive medical devices. At the same time, the pandemic also diminished the ability of hospitals to perform optimal infection prevention and antibiotic stewardship activities as resources were diverted to COVID-19 response …