Special thanks to Paul A. Offit, MD, Director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and Professor of Pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, for this for this guest blog post addressing frequently asked questions about vaccines.

Q: Are vaccines safe?

A vaccine is safe if its benefits clearly and definitively outweigh its risks. But any medical product that has a positive effect—whether it is a drug or a vaccine—can have a negative effect. So no vaccine is absolutely safe. All vaccines that are given as shots can cause pain, redness, or tenderness at the site of injection. Nothing is risk-free, but the risks of vaccines are small.

Probably the most dangerous aspect of getting a vaccine is driving to the doctor’s office to get it. Every year, about 30,000 people die in car accidents and even walking outside on a rainy day isn’t entirely safe—every year in the US, about 100 people are killed when struck by lightning. While routine daily activities pose a certain degree of risk, we choose to do them because we consider that the benefits outweigh the risks. For children who don’t have preexisting medical conditions that preclude getting a vaccine, the benefits of every recommended vaccine outweigh its risks. Before they are licensed, vaccines are tested in tens of thousands of individuals to determine whether vaccines cause common or even uncommon side effects.

Q: Why do vaccines contain dangerous products like mercury?

Preservatives are used in vaccines to prevent severe and occasional fatal infections caused by contaminated vials. The use of a mercury-containing preservative in vaccines harkens back to a statement made by a seventeenth-century chemist named Paracelsus: “The dose makes the poison.” In other words, although large quantities of a particular substance might be harmful, small quantities aren’t. Indeed, everyone living on the planet has very small quantities of a variety of heavy metals in their bodies. All of these substances can be harmful in large quantities, but the small quantities we all encounter from exposure to these metals don’t pose a risk.

Q: Isn’t it better to be naturally infected than immunized?

For the most part, the immune response following natural infection is better than that induced by immunization. Whereas a single natural infection often induces protective immunity, it often takes several doses of a vaccine to induce protection. The problem is that natural infection occasionally comes with a high price: paralysis caused by polio, bloodstream infections caused by Hib, severe pneumonia caused by pneumococcus, permanent birth defects caused by rubella, and cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), to name a few. Interestingly, some vaccines induce immune responses that are actually better than natural infection, including HPV, tetanus, and Hib vaccines.

Q: Why can’t vaccines be combined to lessen the number of shots?

Researchers have been combining vaccines for more than five decades. In the 1940s, they combined the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines into a single shot. Then, in the early 1970s, they combined the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines into a single shot. Since then, additional combination vaccines have been developed and have reduced the number of shots but none have dramatically reduced the number of shots that children need in the first few years of life.

So, why not a single shot that combines all required vaccines? Unfortunately, it’s a lot harder than it sounds. Buffering agents (to prolong shelf life) and stabilizing agents (to evenly distribute the vaccine throughout the vial) for different vaccines may not be compatible when they are combined. Perhaps the best hope for relieving the burden of so many shots would be to start giving more vaccines by mouth or skin patch—technologies that are currently being developed.

Q: Why not use an alternative vaccine schedule?

During the first few years of life, children can receive as many as 26 separate vaccinations and five shots at one time. For most parents, it’s hard to watch children injected again and again with so many shots. So it’s easy to appeal to the sentiment that it might be of value to create an alternative schedule that separates, delays, withholds, or spaces out doses of vaccines.

The perceived value of an alternative schedule is that it might avoid weakening, overwhelming, or altering the immune system of a young child. However, abundant evidence shows that this is not the case. The biggest problem with an alternative schedule is that it increases the time during which children are susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases. If immunization rates across the US were about 95%, this wouldn’t be a problem. Parents could hide their children within a highly protected population knowing they wouldn’t be hurt by bacteria and viruses. But unfortunately, that’s not the case. Parents who make the choice to delay vaccines are taking an unnecessary risk without deriving any benefit.

To learn more about addressing concerns about vaccines and using vaccine safety data to communicate effectively, register to attend the NFID Spring 2017 Clinical Vaccinology Course on March 10-12, 2017 in Chicago, IL. Early registration rates are valid until February 1, 2017.

To join the conversation, follow NFID (@nfidvaccines) and Paul Offit (@DrPaulOffit) on Twitter using the hashtag #NFIDCVC, like NFID on Facebook, join the NFID Linkedin Group, and subscribe to NFID Updates.

Related Posts

Overcoming Barriers to Vaccination

NFID Medical Director Robert H. Hopkins, Jr., MD, shares his thoughts on communication tactics and other strategies to help overcome barriers to vaccination

Sharing Best Practices

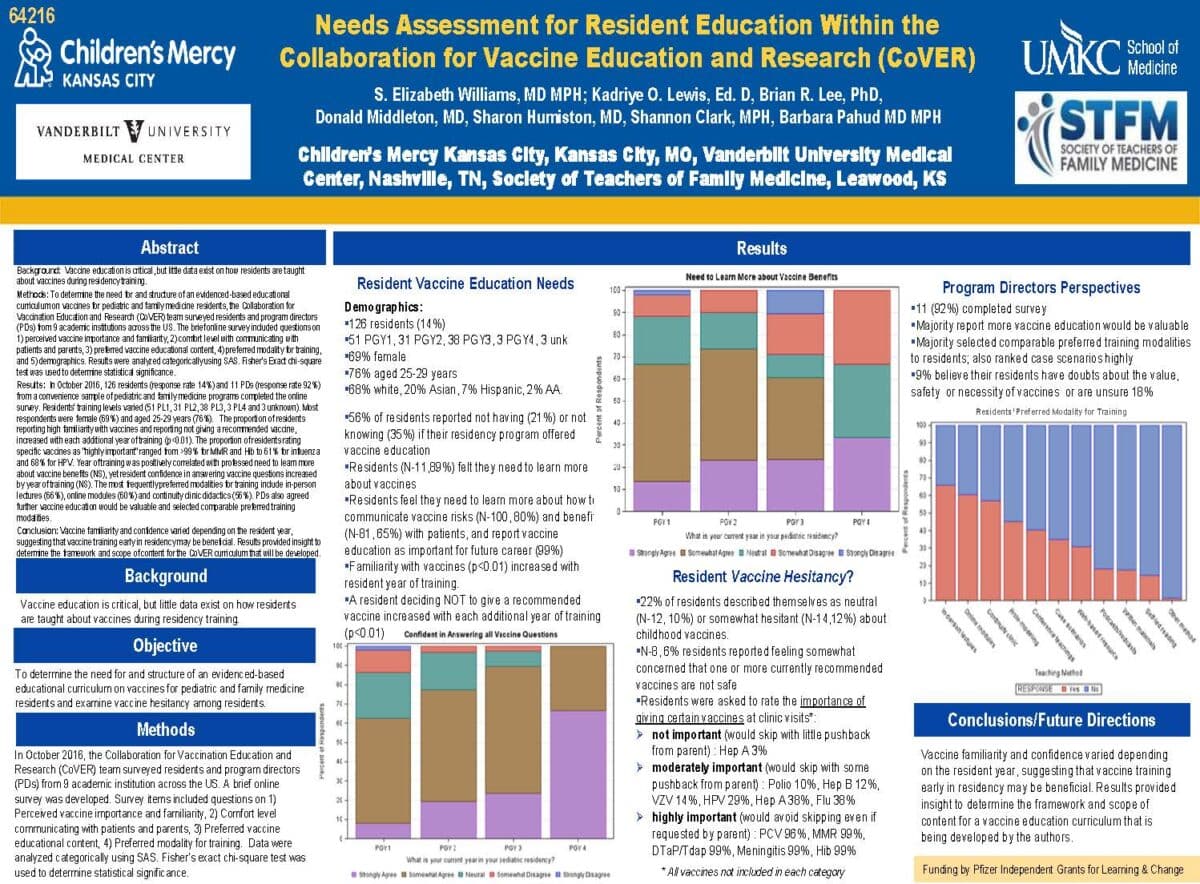

The NFID Clinical Vaccinology Course encourages sharing of best practices through poster presentations and interactive sessions led by expert faculty featuring the latest information on updated vaccine recommendations and innovative and practical strategies for ensuring timely and appropriate immunization…

Travel Vaccines: Know Before You Go

Planning to travel overseas this summer? Before any international travel, it is important to talk with a healthcare professional about recommended vaccines, depending on the country or countries you will be visiting. Vaccines can help protect you against a number of serious diseases, including typhoid and yellow fever, which are found in some developing countries.