Special thanks to C. Mary Healy, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics in infectious disease at Texas Children’s Hospital and director of the Vaccinology and Maternal Immunization Center for Vaccine Awareness Research, for this guest blog post sharing strategies to communicate with vaccine-hesitant parents during National Immunization Awareness Month (NIAM).

C. Mary Healy, MD

No two parents are the same. And when it comes to vaccines for their children, parents can range from being pro-vaccine, to anti-vaccine, to somewhere in the middle simply looking for reliable and accurate information about vaccines. Regardless of the category they fall into, you may find that similar information—be it science-based, anecdotal, or a mix of the two—works for communicating with most parents.

Many attempts have been made to classify the various types of vaccine-hesitant parents, in determining whether different strategies may work better to overcome their fears and concerns. Scott Halperin, MD, identified five different vaccine-hesitant parents. Here are some strategies that may be successful in communicating with these type of parents:

1. Uninformed But Want To Become Informed:

These parents typically get their vaccine information from friends or relatives. These types of parents are turning to you, as a healthcare professional, because of your expertise and they want you to assure them that vaccines are safe and effective. As their child’s healthcare provider, it is important to educate them. Listen to their concerns and explain the science in easily understood terms without using too much jargon. Sharing experiences that demonstrate the benefits of vaccines or telling them about how your child(ren) are fully vaccinated and that vaccination is something you strongly recommend, may be helpful.

2. Misinformed But Correctable:

The media and ease of anonymity online make reporting anti-vaccine arguments easy regardless of the strength of the evidence that vaccines are safe and effective. Many of these articles and social media posts exploit parents’ worse fears. When addressing parents that bring up inaccurate information and stories, it is important to provide sound data debunking these myths. Make sure that you acknowledge the risks and limitations of vaccines and respect parental authority, but be very clear to balance these against the strong benefits of vaccines.

3. Well-Read and Open-Minded:

These parents are aware of pro- and anti-vaccine arguments. They bring a wealth of questions and concerns to the appointment and will need your help assessing the merits of each argument and placing them in a proper context. Walk through each concern and be prepared to have a list of your own sound data from respected well-known organizations, referring them to appropriate websites if they so desire. Lastly, if a parent expresses extreme worry or doubt, contact them after the visit. A reassuring call or email after a visit provides comfort to parents and reinforces the trust you are building.

4. Convinced and Content:

These parents are convinced vaccines are bad but come to you to “prove” they are open-minded. Ask them what it is about vaccines that make them believe they are bad and be prepared to acknowledge their concerns but to strongly refute them with scientific data. They may have specific questions about whether vaccines cause autism, the number of vaccines recommended, or vaccine ingredients, for which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has sample responses available in Talking with Parents about Vaccines for Infants.

5. Committed and Missionary:

These parents tend to be card-carrying anti-vaccine activists who try and convert you to their position. Establishing and maintaining trust with these parents is vital to helping them accept the information you provide. As their child’s healthcare provider, while it is important to respect their opinion, it is necessary to explain the importance of vaccines for the overall health of their child. Refocus the conversation onto the positive effects of vaccines, while letting them know the risks and responsibilities of not vaccinating their child. If a parent refuses to vaccinate, you may want to share the If You Choose Not to Vaccinate Your Child, Understand the Risks and Responsibilities fact sheet. You should also commit to continuing the dialogue about vaccines during each visit, and then make sure to do so. Be patient, as correcting anti-vaccine myths and changing parent attitudes does not happen overnight.

Additional resources to help you communicate with vaccine-hesitant parents are available at:

www.family-vaccines.org/hcps/communicating.

To join the conversation, follow us on Twitter (@nfidvaccines) using the hashtag #NIAM15, like us on Facebook, join the NFID Linkedin Group, and subscribe to NFID Updates.

Related Posts

Protecting Children as They Head Back to School

As school gets underway, experts from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID) offer insights on childhood immunization

Lifelong Conversations about Sexual Health

Teen Health Week is April 4-10, 2022, and STD Awareness Week is April 10-16, 2022, both of which provide an opportunity for healthcare professionals to begin lifelong conversations with patients about sexual health and the importance of staying up to date on all recommended vaccines …

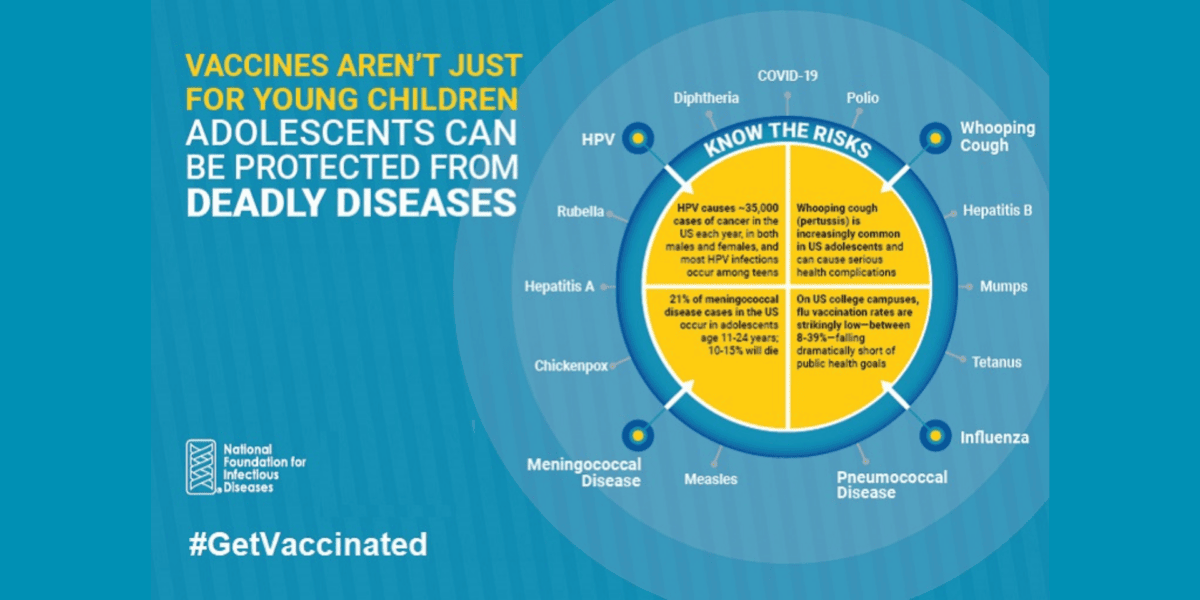

Vaccines Are Not Just for Young Children

CDC recommends vaccinations from birth to adulthood to provide a lifetime of protection. Yet many adolescents are not vaccinated as recommended, leaving them unnecessarily vulnerable. International Adolescent Health Week (March 20-26, 2022) is a perfect time to make sure that pre-teens and teens are up to date on all recommended vaccines …