Special thanks to Karen Ernst, MA, of Voices for Vaccines for sharing her expertise in this guest blog post on communicating the science of vaccines … even with your relatives.

For many families, a large gathering around a table filled with turkey, potatoes, and a can-shaped slab of cranberries is the pinnacle of autumn joy. Aunt Susan asks you to pass the gravy, Cousin Greg compliments the turkey, and Uncle Harold tells you he doesn’t know why you went out to get a flu vaccine because those things are hoaxes.

For many families, a large gathering around a table filled with turkey, potatoes, and a can-shaped slab of cranberries is the pinnacle of autumn joy. Aunt Susan asks you to pass the gravy, Cousin Greg compliments the turkey, and Uncle Harold tells you he doesn’t know why you went out to get a flu vaccine because those things are hoaxes.

Now what? You may be tempted to let his comment go and change the subject. If you are certain that everyone around the table knows not to listen to Uncle Harold, that is a reasonable course of action. But in larger gatherings, people rarely agree so universally with one another.

Dealing with Vaccine Misinformation

The trouble with letting Harold be Harold is that even off-handed remarks can create doubt that is difficult to undo when those doubts are given time to fester. The time to deal with vaccine misinformation is immediately. And the way to deal with it is through building connections and expressing empathy.

That’s not the way it usually goes. We usually deal with the Harolds of our lives by using sarcasm or being dismissive. I mean, sure Harold. Flu shots aren’t real, we never went to the moon, and Paul McCartney died and was replaced by a fake Paul. Sure. But the others in the room who may be at least curious about this vaccine claim, hear only condescension. No one is swayed by sarcasm.

In a clinical setting, when healthcare professionals are faced with a vaccine-hesitant patient, they can employ motivational interviewing techniques. Motivational interviewing is a team effort to help the patient make positive changes in their life. It is a type of conversation where both the patient and the healthcare professional work together to boost the patient’s motivation and commitment to reconsider immunization. According to Professor Julie Leask from University of Sydney, the conversation begins with eliciting concerns, moves to summarizing those concerns and setting an agenda for the conversation, and then goes on to evoking and reinforcing change. Before giving recommendations, the healthcare professional gets the patient’s permission, offers information, and asks about their response to the information and recommendation.

4 Ways to Build Trust

But the family dinner table is a different place from the clinic, and we are guided primarily by our desire to prevent the holiday from devolving into a shouting match and to maintain our relationships with our family. Voices for Vaccines has built a method as a way for non-healthcare professionals to use the basics of motivational interviewing to have constructive conversations about vaccines that are honest and won’t ruin dinner.

The 4-A method is summarized as:

- Ask: Elicit more information about the main concern

- Acknowledge: Build connections to the person by acknowledging what you have in common, what you agree about, or where they are correct

- Affirm: Asking questions and seeking information is reasonable, and many people have these same doubts

- Answer: Get permission to provide your perspective about the concern or facts about the vaccine

Instead of brushing Harold’s concerns off with a derisive snort or with sarcasm, we can enter into a conversation with him by using our own curiosity and asking him to tell us more. Why does he think flu vaccines are a hoax? What are his experiences that lead him to believe that? Rather than swooping in to provide the answers reflexively, we build trust with Harold by listening to learn more about his thought process, rather than listening to respond to what he is getting wrong.

In fact, we work hard to respond to what he gets right. Acknowledging our points of agreement or even our commonalities goes a long way in building trust. It is also a platform on which we can build a change in behaviors or beliefs. Can we get Harold to agree that perhaps vaccines do some specific good?

We can also affirm that his beliefs are not uncommon. Maybe we have heard these concerns before from others, or maybe hearing them now, we understand that it would be difficult to agree to vaccinate under these circumstances. Our empathy not only helps build trust with Harold, but also shows us to be the kind of person anyone at the table can come to with questions and concerns. Isn’t it better that they come to us than Uncle Harold or the guy from their high school gym class?

Now we tell Uncle Harold all about how flu vaccines are not a hoax, right? Wrong. Answering is a process that begins with getting permission from Harold by saying something like, “Would you be interested in my thoughts about why flu vaccines are important?” Most people will say yes, and then we can offer facts, thoughts, experiences, stories, and whatever we have that makes our case. Offering rather than forcing better information about vaccines respects the other person’s free will and right to think as they wish. And it also puts good information out to the rest of the table.

When we sit at holiday tables with the Harolds in our lives, we may feel a need to make sure the facts are corrected. The 4-A process puts the facts last for a simple reason: You cannot get a loved one to listen to you when you put facts ahead of your relationship with them.

“Fostering a respectful relationship is the most important tool we have to change vaccine beliefs and intentions.”

Share the #GiftOfHealth

Share these infectious disease memes to help spread awareness, not disease this holiday season. Tag your friends and family to remind them to #GetVaccinated to help stay healthy!

To join the conversation and get the latest news on infectious diseases, follow NFID and Voices for Vaccines on X (Twitter), like NFID on Facebook, follow NFID on Instagram, visit NFID on LinkedIn, listen and subscribe to the Infectious IDeas podcast, and subscribe to receive future NFID Updates.

Related Posts

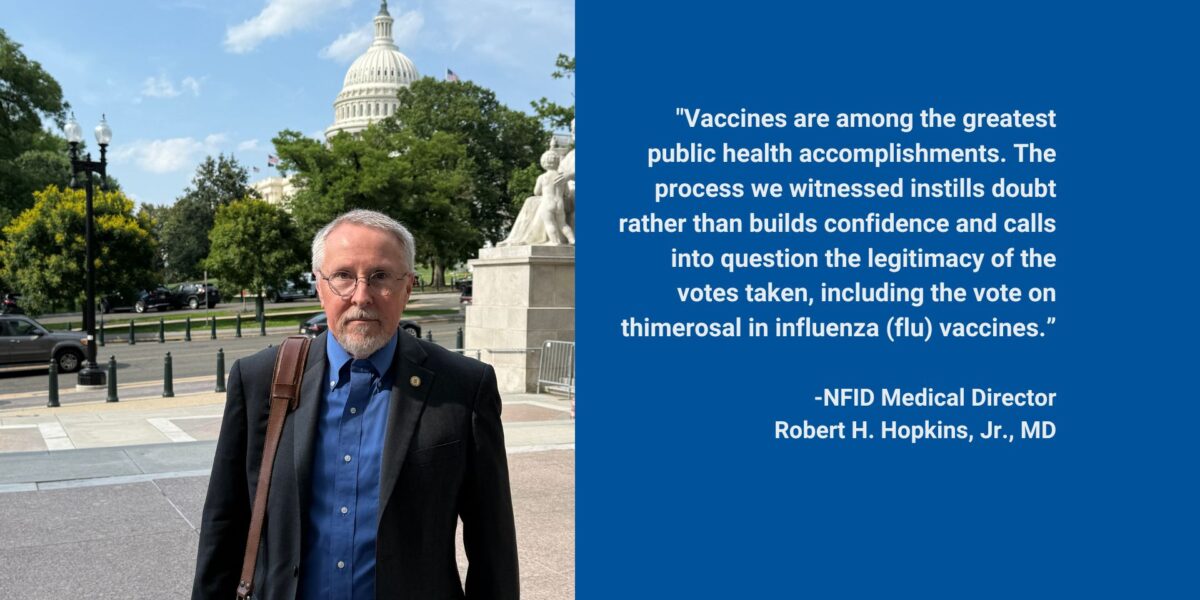

Flawed ACIP Process Leads to Confusion and Distrust

Public health experts and leading healthcare professionals share concerns regarding the June 2025 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meeting on US immunization policy …

Empowering Men to Prioritize Health

Staying up to date on all recommended vaccines and taking other steps to prevent illness helps ensure men are ready for what matters most—showing up for loved ones or simply enjoying life …

Autism and Vaccines: What the Science Really Says

Progress is being made in the search for the causes of autism, and this information may be valuable for families who are hesitant about vaccines